The Temple of Heaven in Beijing

At the dawning of the new year of the Dragon, I found myself consulting the many articles dealing with Chinese cosmology. Some of what I read made sense. It seemed logical enough that everyone born under the sign of the Rooster would not get along with Snakes since serpents were known to bedevil chicken coops. Then again, Dog people should never choose a Tiger as a mate. A tiger, for all its fierce stripes, is really a big cat and we all know what cats and dogs think of each other.

Then, I came to the prediction that things did not augur well for those whose birth animal was the Pig since dragons liked to devour swine. This seemed straightforward at first. Yet when I pondered the matter more, I remembered what every school child will tell you: that the answer to the question, “What do dragons eat?” is a resounding: “anything it wants to”! So I asked myself, shouldn’t the other signs - monkey, horse, etc - be careful too? After all, dragons were clearly at the very top of the food chain and everyone else is surely going to be dinner.

Such reservations not withstanding, it is quite apparent that there is much to celebrate in Chinese cosmology. After all, its precepts have guided one of the world’s greatest civilizations for centuries. It can be seen for example, how the lay-out of the Forbidden City in Beijing is in keeping with the order of things as conceived by the rulers of China. This great palace has a stream in front and a mountain at the back, an auspicious arrangement mirrored by countless villages throughout the Empire.

The Forbidden City is also situated at the very heart of four sacred edifices which represent important elements in the Chinese universe. To the South was the Temple of Heaven built in the 15th century. Its counterpart to the North was the Temple of the Earth. Meanwhile at the East and the West were shrines dedicated to the Sun and to the Moon. The palace’s prime position at the center of this configuration confirmed the monarch’s pivotal role in maintaining the harmony of Nature’s forces.

Lay-out of the Temple of Heaven complex

Every year, the Emperor was supposed to offer sacrifices to ensure that the balance was maintained. The whole court would travel in procession to the Temple of Heaven or Tiantan for the ceremony. Special robes were required, meat was forbidden and there was even a special abstinence pavilion. Each step of the ritual had to be carried out flawlessly otherwise the planet’s future would not be bright. By the time that the ceremony was banned in 1911 by the Republican Government, it had been performed 654 times by 22 emperors of the Ming and Ching dynasties.

Old photo of sacrificial altar

During my own visit to Tiantian, I thought about this long line of rulers going about their imperial duties. Did they fully understand the cosmic importance of what they were doing? Were they nervous? What if they dropped a sacred vessel? Or were they just bored?

As I walked with a friend down the processional avenue which connected the pavilions, it occurred to me: would the emperors have travelled down this same path in a jaded silence? Or would they have been chatting with their courtiers? Would they have been discussing matters essential for the well-being of the Empire? Pretending to be a pompous palace official, I turned to my friend and asked, “Your Majesty, in what shade would you wish the new chambers to be painted?” Upon which my friend replied with as much gravity as he could muster: “Do you have color swatches?”

The cylindrical pavilion sits atop a series of circular platforms in the middle of a square courtyard

As we wandered about I could not help but consider how everything was conceived around certain essential symbolisms which were again rooted in the nation’s ancient philosophies. Foremost in this foundational iconography was the image of the Circle and the Square. The Chinese believe that the idea of Heaven is best expressed by a circle while a square is thought to capture the qualities of Earth. For a circle is dynamic, always ready to roll away. Similarly the sky is protean, changing colors throughout the day. In contrast, both the square and the earth are fixed like the solid ground beneath are feet. These notions are encountered in other cultures as well.

Squares and circles in a mandala

One can see that in the great mandala paintings of India and Tibet, the central objects of meditation were the Circle and the Square. Likewise, in Islamic architecture, a dome set on cube-like structure was following a similar principle.

In the case of the Temple of Heaven, our guidebook explained that even the perimeter of the entire compound consciously emulated the Divine Pair. The northern end curves while the southern end forms a box. Then again the most important buildings of the complex along with the platforms on which they stood were round but the vast paved enclosures in which they stood were square. This arrangement is easily discernable if one were to look at the structures from the air.

By far the most remarkable edifice in the entire compound is undeniably the great Hall of the Prayers for Good Harvest. Due to its celestial affiliation the Hall is appropriately circular. One first glimpses the hall as one goes through the great gates that open into a terrace which provides a spectacular vantage point. The visitor is well-advised to pause, to savor what is unfolding. Viewing it, that cold Spring morning against the backdrop of a blindingly blue sky, I got the aching feeling that I was in the presence of one of humanity’s masterpieces.

Perfection in a building: the Hall of Prayers for Good Harvests

Perhaps the Hall’s allure has something to do with the fact that there is nothing else behind it. Despite the overcrowded conditions of Beijing, the authorities have to seen to it that no other building competes with this splendid creation. Though it soars to a height of more than a hundred feet, the wooden Hall does not contain a single nail. Its central space is uninterrupted by beams, making it easy to understand why this was considered, for centuries, as a spot where one could commune with the Gods.

Perhaps it is the way the pitch of the roof fans out ever so slightly or how the sensuous curves of the walls are echoed by the eaves. Whatever it is, I was mesmerized. I could not tear myself away. One other sight which had the same effect on me was Mount Mayon in Bicol. Its unblemished cone was equally hypnotizing. Even as my vehicle hurried past I had to open my window and twist around for an additional glimpse until my neck ached. How often does one have the chance to bear witness to perfection?

Cylindirical column on a square base

Square grill with circular opening for a cylindrical tree

The Circle and the Square on a sidewalk in Beijing

Back in Beijing, my friends had difficulty convincing me that it was time to go. Worse, I drove everyone mad because I was beginning to see the Circle and the Square everywhere. I saw the cosmic pattern in the cylindrical columns set on their bases. I saw it in railings, on the sidewalk, on the facades of offices. Much later, I would even see it in temples and shopping malls, in the packages of food and in the embroidery of costumes.

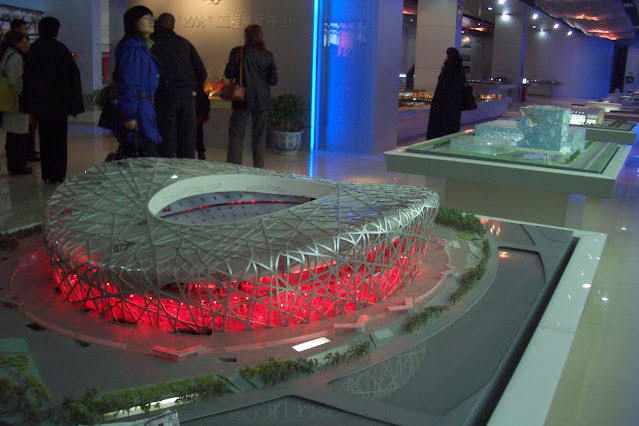

On the ride back to our hotel, I was suddenly enlightened: why, even the two most celebrated buildings which were set up for the Beijing Olympics conformed to the great symbols of Heaven and Earth! Yes, the Stadium which had been nicknamed the Nest was a circle while the aquatic sports pavilion was a Square. When I shared this wonderful observation with my exhausted friends, my brilliant insight was met with howls.

The Stadium for the Beijing Olympics 2008

The Beijing Oympics Aquatic Center

My opinion about how my wisdom was received was best summed up by a saying involving pearls and swine unrelated to the Chinese Zodiac. But I am certain that the great cosmologists of China would have approved of my efforts. They would have been pleased to know that after so many centuries, the patterns identified so long ago to explain the inter-relationship between the Heavens and the Earth continued to be honored even in the present day

,%20Dr%20Teresita%20Habawel-Kalugdan,%20Argel%20Geralde,%20Nezi%20Nulduan,%20Yolanda%20Binwag%20and%20Flor%20Amamhic%20.JPG)